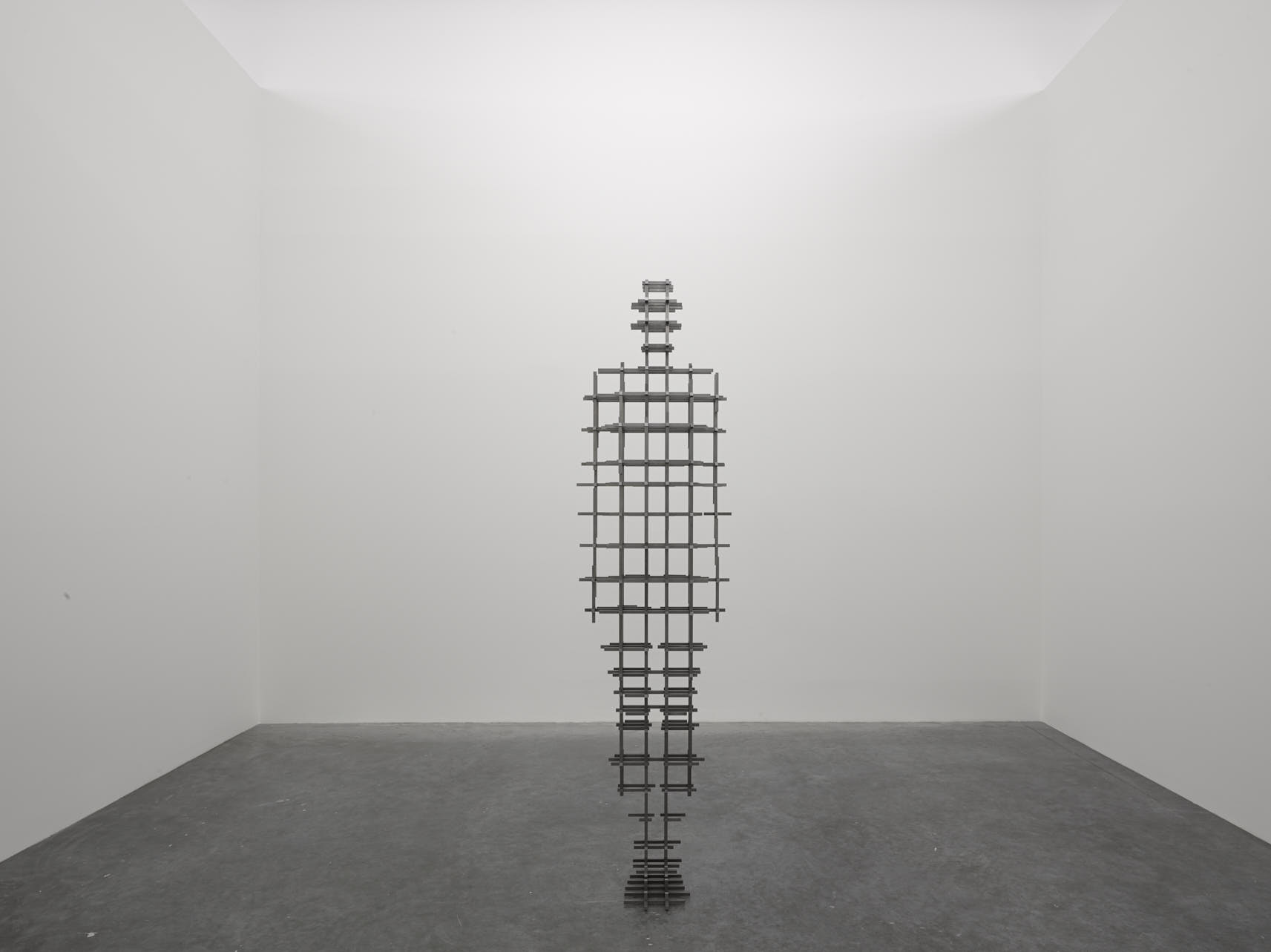

'The work that bears the peculiar name MEAN takes meanness to an extreme. The piece forms part of a recent series of steel grid works in which the body is reduced to a lattice of pure Cartesian co-ordinates expressed in three dimensions, and then subjected to further reduction. This specific series marks a relatively new stage in Gormley's artistic trajectory, but the concern with measurement is itself nothing new, and this particular project can be seen as an extension of his earliest experiments. The grid has never been all that distant. Even those bread slices - that doughy mattress from which the 30-year-old Antony Gormley had once eaten out the contours of his own body - had been lined up meticulously in rows and columns like a giant chessboard [BED (1980-81)].

The early lead body cases were also gridded: silvery scars of solder ran across the surface of the body where the black sheeting hammered to the fiberglass shell had been sutured together in vertical and horizontal sections, like the co-ordinates on an atlas or on a butcher's chart. But whereas in the early works the body had been overlaid by a grid, in this recent series the body has dissolved into the grid: it has become nothing but a three-dimensional Cartesian diagram of itself. The grid no longer adheres to the surface of the body but rather occupies the entire volume of the body. There is no body - only the vestigial co-ordinates of a body that has been abbreviated to its minimal internal geometry.

MEAN (2016) presents an abbreviation of this rudimentary abbreviation. Having reduced the body to a grid, the artist proceeds to 'mine' this grid - he removes meaning from meanness - until the structure as a whole becomes as patchy as moth-eaten lace: he depletes the grid of its vestigial materiality and dimensionality by subtracting segments of the steely carcass until the object retains nothing but the minimum of support and structure necessary to keep standing.

The grid becomes a cipher of itself - no longer a grid but the barest sketch of a grid in which we can read the suggestion of a human body. That this work exists at life scale only accentuates the degree of the abridgement. It also establishes, if there were still any doubt about this, that this is not an image or representation of a human body: it is not a question of one thing standing for another, but rather the literal occupation of a body's space by its own co-ordinates. But the process of reduction goes even one step further. Framed by the doorway, that is, contained by a manifestly architectural setting, the work takes on the appearance of a two-dimensional drawing. Because of the near-symmetry of back and front, the intensely graphic frontal view gives no hint of the side view, or even suggests that there will be one. The visual transparency of the figure is accompanied by a complete conceptual opacity: one cannot predict, from looking at the front of the object, what will happen when you walk around it, or even if you will have occasion or permission to do so. Depleted of depth and dimensionality, the object turns into a pure planar surface - the abbreviation of an abbreviation of an abbreviation. Under the pressure of architecture, the sculpture turns into a drawing, and the drawing in turn leads back into architecture. A slight shift of perspective transforms this human stick figure into an architectural floor plan.'

Rebecca Comay, ANTONY GORMLEY: FIT, London: White Cube, 2016, p. 107-108